"The biggest challenge for me has been to really understand who I am.”

Ian Smith

– reflects on his late autism diagnosis and his fight for more inclusive workplaces.

In this Stories from the Spectrum feature, we caught up with Ian Smith, a Change and Transformation leader at Zurich Insurance Group. In his recent poem, A no hope daydreamer (done okay), Ian reflects on his experiences growing up as an undiagnosed autistic child and how he has used being autistic to achieve success and fight for more inclusive workplaces.

We spoke to Ian to find out what inspired him to write his poem, the impact that being diagnosed as autistic in his late 40s had on his life, and his advice for other autistic people to succeed in a leadership role.

What inspired you to write your poem, A no hope daydreamer (done okay)?

It was one of those reflective pieces. One day I sat down asking myself: “What is happening with my life? Where have I come from? What has my journey been from being a child to where I am today?” Then as I wrote it, I thought, “I could make this into kind of a rhyming thing.” Originally, it was just thoughts on a page that naturally formed into stanzas, and then with a little bit of work, I developed the ideas into rhyme.

When did you first know or start to think you were autistic?

I knew very little about any neurominority groups until only five years ago. I've got two teenage children who, for differing reasons, were struggling with their mental health. This culminated in identifying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for my eldest in 2018, and both children were identified as being on the autism spectrum in 2021.

As we completed the assessments, I came to the realisation that I shared so many of the traits and characteristics of both conditions, so I started my own journey of assessment and knowledge acquisition around the different neurotypes. I was highly self-aware, but I realise now that I am only just starting to understand the complexities of me.

What impact did being diagnosed as autistic have on your life?

It’s been an absolute game changer. I realised that with a very literal interpretation of the world, when interpreting requirements, I might put too much emphasis on certain words. For me, this new understanding was key because I have been able to find ways of communicating more effectively to make sure that I understand others and they understand my requirements.

Since my diagnosis, I have been very open and honest with my managers, colleagues, and those around me to explain how my conditions present, and how through understanding, we can collaborate effectively together. I have found that by being open about my vulnerabilities upfront, others can learn how to work and adapt to me, and then we can work together to get the best out of our relationship.

Growing up, what was school like for you?

I hated going to school. I was treated like a complete and utter idiot. Because of my dyslexia and dyscalculia, my motor skills weren't there to be able to form the words or to copy text from the board. I was held back at breaks. I was told I was an idiot. And that stuck with me my entire school life.

The whole way that the school system was set up for me just didn't work. It wasn't designed in a way that enabled me to keep up pace with the rest of the kids, which made me think I was really, really stupid. But then I was reading lots and lots of books at home that were significantly ahead of what was being taught within the school. There was this huge disconnect with what my actual capability was because, in the 70s, there was little to no understanding of neurotypes.

In your poem, you say that you “found inclusion in drama”. Could you tell us a bit more about your interest in drama, and how it helped you to find “inclusion”?

When I was 11, I joined Youth Theatre Yorkshire after performing in the chorus for a show at York Theatre Royal. I enjoyed it, as I was allowed to learn new skills and just be me. It developed my social skills, my confidence to speak to others, and it helped me to just come out of my shell. This was me being me and learning to find myself.

I noticed a lot of patterns in my autistic daughter’s behaviours that were very similar to mine. So when I saw that there were auditions locally for Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat, I said to her: “Why don't we go and audition for this?”. Nervously, she agreed and joined the chorus. Since then, she has gone on to perform in other shows and we now have this shared interest.

Seeing the change in her from being shy, an introvert, disliking being around people, to developing herself, gaining confidence to get up on stage and take on lead roles – it’s been transformational. I would suggest that anybody who has autistic children explore ways to get them to look at drama.

But I am proud making ground, By sharing my story, Championing the fight of Neurominorities, Pushing for equity and inclusion, not glory.

What challenges have you faced as an autistic person?

I have learnt to mask, to mirror, to change and become whatever I thought I needed to be within the situation that I'm in. The biggest challenge for me has been to really understand who I am: where do the traits of the conditions end that I have been trying to mask for all this time, versus me as the individual?

Because I have got my multiple conditions, it is also trying to separate which bits are what. I like to be social because of the ADHD and I want to be at the centre of attention, but I also want to be alone in a room with my own thoughts, often because I have been too big and boisterous, feeling drained of energy.

How has being autistic helped you to succeed in the workplace?

I think I have been able to succeed because I am able to see the patterns that others don’t see immediately and say what I see in a way that others feel unable to. I am a programme director for complex international projects; my skills help to see the critical path in my programmes and spot emerging risks, ensuring that we deal with them in the right way. It is that ability to see the holistic picture, to know when to get into the detail and when to take a step back, that has really helped me to drive value in the workplace.

In your poem, you say that you use your “privilege as an autistic employee… to champion inclusivity”. Could you tell us a bit more about how you have used being autistic to push for inclusivity in your workplace?

I am employed as an autistic person in a leadership role and feel that autistic people and people from other neurodivergent groups have so much to add. I have a voice and I use it to help influence and remove to barriers to entry, to change employment policies and working practices. I have championed a universal design approach, to ensure that more opportunities to really flourish within the workplace exist for everyone.

I have become quite core within the Zurich Accessibility Inclusion Network, looking at how can we improve employment opportunities for autistic people. Zurich is changing practices within the UK and EMEA to ensure that we have more inclusive cultures and ways of working that address the different support needs of all neurotypes within the workplace.

My master’s thesis in 2021 explored how to improve neurodiversity attraction, recruitment, retention, and development. I have been fortunate to work with Zurich to explore the findings and recommendations that we found. For example, we are starting to see that interview questions may be shared in advance, and starting to interview for skills rather than competency-based questions, which are discriminatory against neurotypes that process the world in a literal sense. It is a simple change, but it's a game changer.

Could you tell us about your experience of being a parent to two neurodivergent children?

It is been hugely challenging, but the most rewarding part of my life because I would not change either of them for the world. Without realising that our children were neurodivergent, we adapted our parenting style to hopefully be as supportive as we could of them and just allow them to be them.

I wish I had known earlier that my kids had the conditions that they had, but I think now that I understand them, they understand me. It has helped us to get to a better point as they are older, where I understand what their nuances are and how I can help them in ways that I was not able to before.

What advice would you give to other autistic people to succeed in a leadership role?

Really take the time to reflect upon yourself, to understand how your impact on other people shapes and influences situations and relationships. Look at Dr Damian Milton's double empathy problem: probably the biggest influence to understanding the difference in communication styles between autistic and non-autistic people and how both need to find ways to communicate more effectively.

Be as vulnerable as you possibly can with your team and with those around you. If you can, help people understand where you may need different communication strategies to help you work together, so that you can understand both your peers and your horizontal and vertical reporting structure to get the best out of the relationships. Once we all start working together and communicating together, we can change the world and it will be a better place for all of those who follow us.

Find out more

Read Ian’s poem, A no hope daydreamer (done okay)

Learn how our Autism at Work programme supports employers to attract, recruit and retain autistic employees.

Read more Stories from the Spectrum here.

Similar stories

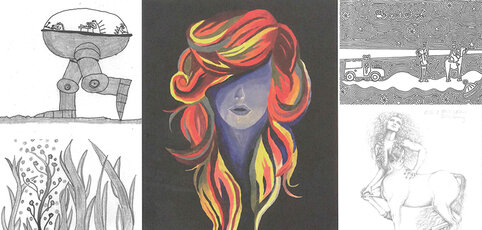

"I have always enjoyed art. I didn't speak until I was five, but I communicated through drawings."

Spencer Cotterell

- on autism, communication, and his love of art

Read more

"Queer culture seems to have an issue with intersectionality, especially towards those with disabilities."

George Morl

- on attitudes towards autism and disability in the LGBTQ+ community

Read more

"I want to give a voice to people who are not often represented in pop culture."

Iqra Babar

- on representing BAME autistic people through her art

Read more

The Spectrum magazine

Explore one of the UK's largest collections of autistic art, poetry, and prose. The Spectrum magazine is created by and for autistic people, and is available both online and in print.

Read the Spectrum

You are not alone

Join the community

Our online community is a place for autistic people and their families to meet like-minded people and share their experiences.

Join today