The Secret Diary of Tré Isaac Age 29 ¾

Tré Ventour-Griffiths - Multiply-disabled Historian, Creative Writer, and Sociologist

For Black History Month we invited Tré Ventour-Griffiths to write a guest blog.

Tré is a multiply-disabled historian, creative writer, and sociologist with interests in Black British histories in the town and countryside, racism and disability, popular culture, life writing, and hauntology. His PhD uses creative writing to consider a multigenerational story of UK Caribbean Northamptonshire Post-1940. Tré’s works in pop culture looks at representation, identity, and political commentaries in the history, writing, and development of popular entertainment namely comics, film, and TV. He has written and presented on work including Jane Austen texts, Barbie, superheroes, and Disney.

Now nearly 30, I never used to think about myself as queer until I began engaging in the scholarly field of Queer Theory, which offered layers that I did not find in the mainstream. When I was 20, it was transgender students who recognised my autism before I did, which then began to show me a possible queer identity beyond sexuality. For example, the late bell hooks talked about queer “… as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” Autistic while Black, I am ‘there’ and ‘not there’: a spectral projection in abled Black spaces and transient in white disability spaces, including Disability Studies and Critical Autism Studies. My personal history and Black present are stories of phantoms.

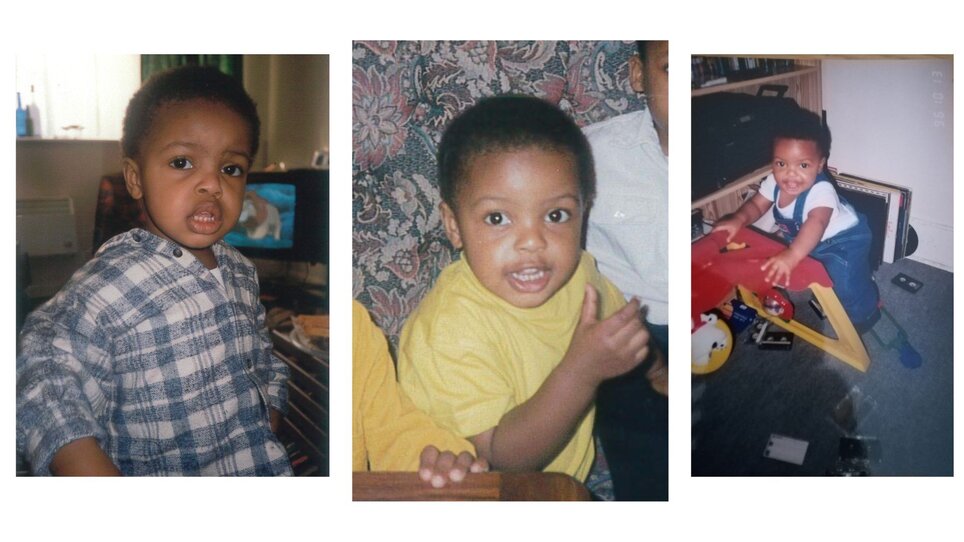

I am someone who people have described as ‘popularly alone’, and I am quite envious of people who have had the same friends since they were children. While I have friends who care about me, they mostly live far away. Many of my friends are also at different points in the life cycle: (new) parents, buying houses, committed relationships, newlyweds – that kind of thing. Nearly 30, finishing my PhD, single, no children, waiting for the latest Avengers film, I feel like I am a teenager for the second time because I was 17 when the first Avengers was released. I am a child of Gen-X parents, but more critically, a child of grandparents whose houses were often full. With people increasingly online compared to my childhood of MSN, Pokémon and Tamagotchi, I find myself stuck in the past.

Autistic while Black, I like to operate in my own time and space. This society isn’t made for the single or childless, especially those of us who are by choice. Time is out of joint: this is what Derrida argues in Specters of Marx, where what we see as ‘past’ is always snapping at the heels of an always elusive present. Into my next chapter, time moves differently here with my slow now and a future out of reach. I don’t always feel time. Abigail Thorn’s video Queer and philosopher Jack Halberstam’s book In My Queer Time and Place, where he coined the term ‘queer time’, allowed me to lean into this idea of being a 30-year-old teenager haunted by an upside-down Wonderland-like future.

What is time, what is space? I don’t have the answers to that, but Denis Villeneuve’s film Arrival helped me feel why my time is out of joint. In the film, the main character, linguist Dr Louise Banks, says: “We’re so bounded by time, by its order. But now I am not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings. There are days that define your story beyond your life”.

It is one of the jobs of historians to analyse the past as ‘what has happened’, but what if you begin to see time all at once? This is the underpinning of the film, but also what is generally believed in western physics – it seems like academic historians have fixed notions of past, present and future as distinct. As a creative, I see time as a suggestion.

With my autistic way of seeing the world, it’s queered how I live. Meg Hopkins wrote: “experiences of queer people like coming out, or transitioning for trans people, warp time which prevents life developing in a linear way.” I loved being a child of grandparents, and now at 30, I feel I am seeing my time spin, having a second wind of childhood. While my experiences of being Black in the UK have pulled me towards work by Black British scholars and writers, my experience of being autistic showed me the limitations of Black British non-fiction (a lot is very linear). Through my autism, I pivoted not to Disability- or Critical Autism Studies (too white) but to Queer Studies. I often feel that although there have been strides in Black British non-fiction, it frequently affirms an abled cis-heteronormative society.

I did not grow up queer, but I found it through being autistic. Finding out I was autistic at 20, I have always known I was different – people generally tell you. Now, I don’t care. Being nearly 30 is about doing all the things I loved as a child, but with adult money!

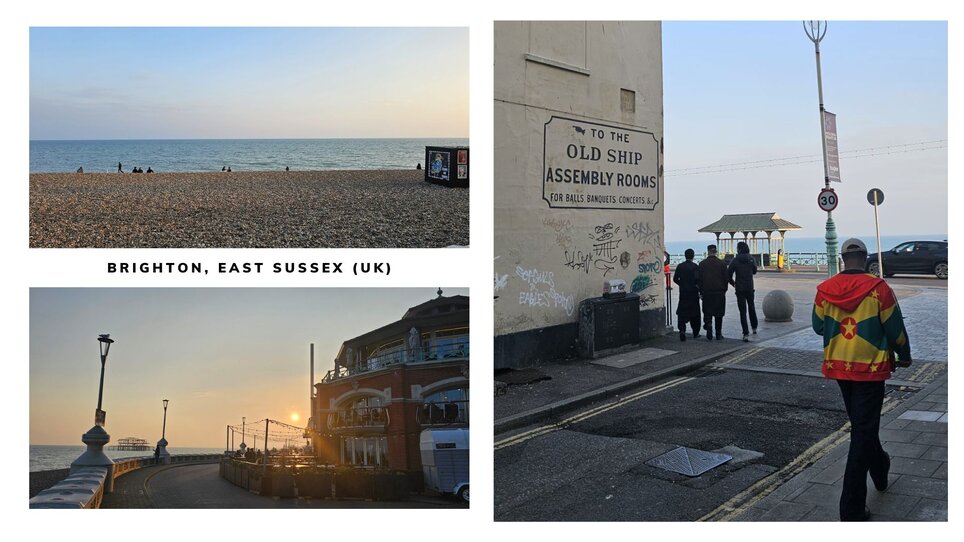

Like how lesbian theorists exposed “academic discourse” in the 90s as just for cisgender straight people, it often feels that writing about Black British history and culture is for Londoners at best, and at worst, for those who are interested in big cities. Who is ‘in charge’ of Black British media and publishing tends to impact what kinds of questions get asked! Those of us who grew up Black but on the margins of urban narratives (such as rural settings) end up learning the histories of where we live through unofficial means.

Like how lesbian theorists exposed “academic discourse” in the 90s as just for cisgender straight people, it often feels that writing about Black British history and culture is for Londoners at best, and at worst, for those who are interested in big cities. Who is ‘in charge’ of Black British media and publishing tends to impact what kinds of questions get asked! Those of us who grew up Black but on the margins of urban narratives (such as rural settings) end up learning the histories of where we live through unofficial means.

Einstein proved time is not the same for all. Growing up in Northamptonshire and having a Caribbean context for our history, my historical time clashes with the official history of the cities and may in fact queer against the Black British mainstream. My PhD threads many local events that were happening at the same time as well-known London histories – it skews time’s passage. There’s a blind spot in Black British history that people may want to consider. In short, the events that chart time’s movement for Londoners may not fit the rest of the country, pertinently those of us in rural areas, the coast, parish and micro-historical – we may queer the urban. When thinking about queerness beyond sexuality, in the ethos of bell hooks and Tim Dean, Black British history is part of this. My personal history is queer, and today, I keep going back to those Black British lost futures trapped in early 2000s recycling. My childhood was wonderful; it was growing up that was hard.

Thanks very much for reading.