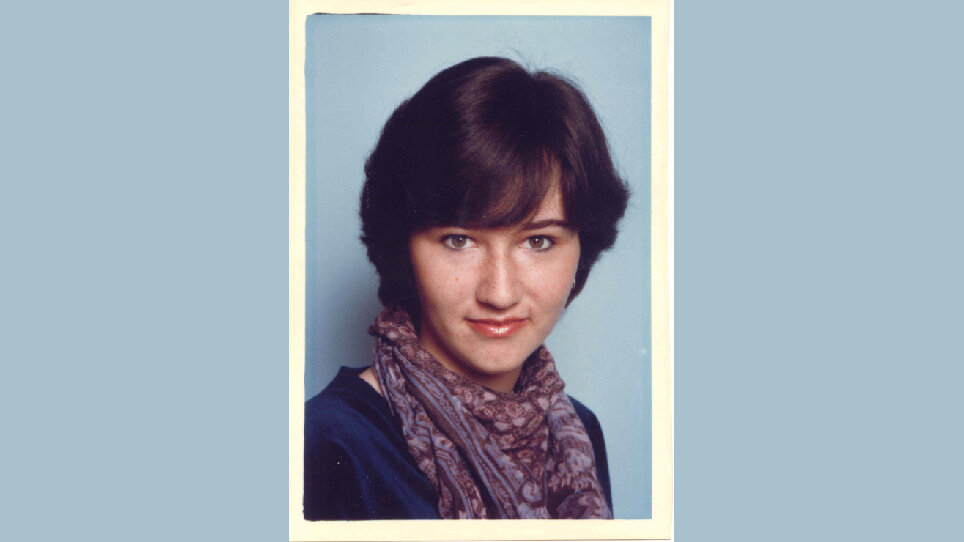

Dawn's story

Dawn, 56, a Data Manager, was diagnosed in the last year. In her full interview, below, Dawn speaks about her passion for yarn and family history. She also discusses the debilitating medical phobias that led to suicidal ideation before her diagnosis at the Lorna Wing Centre.

My story

The yarn in my campaign photograph means quite a lot to me. It's one of many things I've picked up over the years thinking I would just try it and it's then become very addictive. One blanket leads to another one, one pair of socks leads to another one – to wanting to design the most perfect pair of socks. It's more than simple pleasure. It is very relaxing in stressful situations. The crochet socks would follow me on the bus to work and back, for hours every day, and it's a way of tuning out other things that might be bothering me on a sensory level. It's very rhythmic with counting stitches.

It’s not something that’s come with my diagnosis, it's something that has always been a part of me, whether it's the yarn or researching my family history or something else. However, having been diagnosed, I can reflect back on it and realise how integral it actually is in the very fabric of my autism, if you like. That it is more than just a hobby, that it does extend that bit further, that I can get boring at parties about it if you let me. The diagnosis has contextualised something that I just accepted and enjoyed as part of my being.

"How did I feel when I realised I was autistic? That is very difficult to encapsulate. At first shocked and then massively relieved."

How did I feel when I realised I was autistic? That is very difficult to encapsulate. At first shocked and then massively relieved. There is a long story to it. I’ve had lifelong medical anxieties. And as I'm getting older, general medical staff are having to do things to me. This has been a problem my whole life, with very strange incidents happening in those contexts. From being locked up and frozen – unable to move, unable to speak – as a toddler, through to staff having to bash down toilet doors to get me out for treatment, to finally then taking my teeth. There were wall thumping, effing and blinding meltdowns, and I could not understand what was happening to me.

Mental health services did not understand what was happening to me. They put me through the usual therapies and approaches for neurotypical people, which didn't work, and they blamed me. I had got to the point of suicidal ideation and I had been in that state for a good couple of years. And, of course, then we've got a pandemic on top of that, which is bringing up more medical anxiety. I reached a certain point where I just was in the depths of crisis with nowhere to go with this. Going to bed, hoping I wouldn't wake up.

But I think I realised at that point I had to find out what this was for myself, because if I didn't, that really was going to be the end of it for me. They were either going to lock me up or I just wasn't going to make it.

"Mental health services did not understand what was happening to me. They put me through the usual therapies and approaches for neurotypical people, which didn't work."

So, I did two things. I engaged my own counsellor, but I also got onto Google. I knew that nothing mental health services had ever said to me made the slightest bit of sense in terms of what I was repeatedly describing to them. Nothing. So I started looking for a map for my experience, something that would explain it. Looking in scholarly articles, journals, blogs of people experiencing various mental health difficulties. It must have taken me a fortnight going through every psychological disorder known to humanity, I think. Phobias, anxiety disorders, personality disorders. Nothing matched me. I couldn't recognise any of it and I couldn't relate to any of it.

And then finally: the only little clue I had was one article about medical phobia in autistic children and, of course, I glanced over it. Finally, I clicked on one of the links to the National Autistic Society. They'd been coming up all along in my searches, and I'd been hopping over it and hopping over it because how the hell am I autistic? I'm a trainer, I'm no social-phobe, I've got a degree in modern languages, I was good at drama school.

"I started looking for a map for my experience. Finally, I clicked on one of the links to the National Autistic Society, and there was the map."

How am I autistic? But when I clicked on that link, there was the map. There was a descriptor of a meltdown and a shutdown, and I recognised both.

"I looked at the childhood indicators and I realised there was every possibility that I could be autistic. Almost every sensory glitch and childhood experience listed apply to me."

But I'm still scratching my head at this point. I printed it off and took it down to my husband. I said, “This is what it feels like; is that what you are seeing?” And he said it was. I looked at the childhood indicators and I realised there was every possibility that I could be autistic. Almost every sensory glitch and childhood experience listed apply to me. I can't catch a rounders ball. I can't ride a bike. I was bullied at school for being useless at games, for being highly squeamish.

My first day at school flashed before my eyes: I'd expected to be learning how to read and write on day one, but children were playing. I sat at the edge of the room feeling bewildered because I couldn't understand why children were playing at school.

I also very quickly realised that this was the core of what was happening to me in medical situations. It was a sensory assault every time and a complete communication collapse. No wonder I had these destructive relationships with doctors, because I can't take care of social niceties while I'm experiencing Room 101-type abject terror. I'm in the midst of a shutdown or on the verge of a meltdown. I very quickly realised that was the answer to my issue.

"I was diagnosed at the Lorna Wing Centre. And the emotion was enormous relief. I think probably the most intense feeling of gratitude I've ever had in my life."

I knew that in order to be taken seriously I had to have somebody look at this objectively and I wanted the best. I took it to the National Autistic Society and I was diagnosed at the Lorna Wing Centre. And the emotion was enormous relief. I think probably the most intense feeling of gratitude I've ever had in my life.

The National Autistic Society literally saved my life. There's not a shadow of a doubt. But with that comes an awful lot else as well. You then look back over the entirety of a lifetime and it isn't just about these very extreme experiences within a medical context. It makes sense of absolutely everything.

And it's not all bad stuff. There's an awful lot to be celebrated there. And the one thing you just want to do is own it and embrace it. There are a ton of things I can do far more easily than a lot of other people can. For example, when I did some postgraduate stuff, the research methodologies, which are straightforward and easy for me, why was the rest of the class struggling with that? Why am I so good at cracking family history problems that some of my cousins would struggle with? It's to do with the thinking, the logical processes. I have derived both success and enjoyment out of it. This is because I'm autistic.

My neurological system is my neurological system. I am always going to experience what I experience in a medical environment. And in a way that's quite depressing because no amount of CBT in the world is ever going to shift or change it, because my sensory system will do what my sensory system does. But it does open up the door for other avenues to get some help. One part of the NHS that have been brilliant is special care dentistry. They are acutely aware.

"In a medical environment, my sensory system will do what my sensory system does. But there are ways in which that could be mitigated to make it as easy for me as we can."

Some GPs I've met, not so much; they won't accommodate at all. But the avenue is there: if I understand the problem and they understand the problem, then you start to introduce into the equation ways in which that could be mitigated to make it as easy for me as we can. Even if it's as simple as: if I'm not capable of saying ‘Good morning’, don't think I'm being rude.

"Society has some very stereotyped ideas. They think we're all Rain Man or Sheldon. I am also what autism looks like."

I think it's very important that people do understand what autism can look like in subtler presentations and, in particular, women and non-binary people. Society at large has some very stereotyped ideas. They think we're all Rain Man.

They think we're all Sheldon. Or they think we're all that non-verbal kiddie having a meltdown in the middle of a supermarket. And whilst that might well be the expression of autism for some people, I am also what autism looks like.

But beyond the general public's perception, the services need to get it: police, social care, education, health services – general medical and mental health services. I went through a two-year period of contact with mental health services and they did not recognise autism when it was right in their face. As long as those essential services are not recognising autism when they see it, they are letting people down.

There are thousands of other individuals behind me going through the same things with the same level of desperation because they don't understand why they are experiencing what they are. I wanted to take part in this campaign for them. What would I say to my younger self? ‘Hang in there, it will be okay. And just do what you're doing.’ There are a lot of times when I recognise now that I really did hang on to myself against the odds.